"A line shall be drawn along the boundary between the Thana of Phansidewa in the District of Darjeeling and the Thana Tetulia in the District of Jalpaiguri from the point where that boundary meets the Province of Bihar and then along the boundary between the Thanas of Tetulia and Rajganj; the Thanas of Pachagar and Rajganj, and the Thanas of Pachagar and Jalpaiguri, and shall then continue along the northern corner of the Thana Debiganj to the boundary of the State of Cooch-Behar. The District of Darjeeling and so much of the District of Jalpaiguri as lies north of this line shall belong to West Bengal, but the Thana of Patgram and any other portion of Jalpaiguri District which lies to the east or south shall belong to East Bengal."

This is how the report of the Bengal Boundary Commission, commonly known as the Radcliffe Award, begins.

Border drawn in a hurry

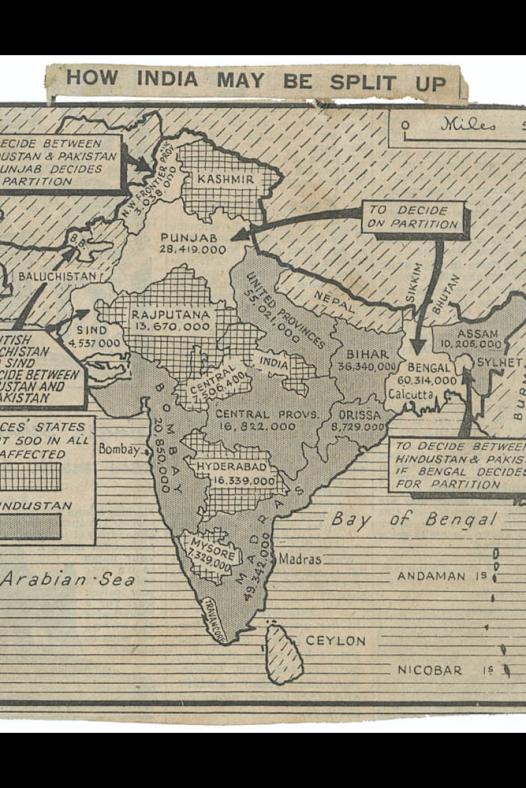

In just nine days of public sittings, during which the chairman of the commission, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, did not attend a single hearing as he was simultaneously involved with the Punjab Boundary Commission, the fate of millions was irrevocably altered. Within this brief and chaotic window, the foundations of a complex modern nation-state were hastily laid.

British lawyer Radcliffe had never set foot in British India before this assignment. Yet he was given only five weeks to divide millions of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs between the two new dominions. During this time, he suffered severe dysentery in the tropical Indian monsoon. Many suggest that his deteriorating health made him desperate to conclude his work quickly, prompting a rushed delineation of the boundary line.

Radcliffe acknowledged the immense practical challenges of drawing a border in Bengal. He admitted that, although he tried to avoid disrupting vital railway lines and the Ganges river systems, such dislocations were inevitable given the constraints placed on him.

Pakistan attained independence on 14 August 1947, followed by India on 15 August. Yet, curiously, the Radcliffe Line was made public only on 17 August, three days after the two nations were born. This meant that the residents of vast frontier regions awoke into independence with no clarity about which country they now belonged to. In many places, this led to chaos and confusion, with multiple flags raised and rival administrations competing for control.

The district of Nadia in undivided Bengal became a dramatic illustration of this uncertainty. It was widely assumed that the entire district would become part of East Bengal, later to be renamed East Pakistan, prompting Pakistan's flag to be raised in several areas. However, political lobbying soon followed. Influential leaders and local aristocrats such as Maharani Jyotirmoyee Devi urged that Nadia be included in India. Their campaign eventually bore fruit. A formal notification (No. 58 G.A., dated 17 August 1947) was issued, whereby the subdivisions of Kushtia, Chuadanga, and Meherpur were designated as the new Kushtia district in East Bengal, a province of Pakistan, while Nabadwip and Krishnanagar were incorporated into India as the newly formed Nabadwip district.

In contrast, the district of Khulna experienced the opposite fate. On 14 August, the Indian flag was hoisted in Khulna. According to the 1941 Census, the district had a Hindu majority of roughly 51 percent, many of them from scheduled castes. This demographic profile led many to believe Khulna would be awarded to India. Yet when the Radcliffe Award was finally published, it became clear that Khulna had been awarded to Pakistan.

The Chittagong Hill Tracts presented another baffling contradiction. Despite being a Buddhist-majority area, the district was handed over to Pakistan. In anticipation of a different outcome, Indian and even Burmese flags had been raised in some areas. Popular discourse has long suggested that the inclusion of Khulna and the Chittagong Hill Tracts in East Bengal served as compensation for the loss of the Calcutta port to India. While Radcliffe justified Khulna's inclusion by citing its stronger transport links with Jessore, the rationale for the Chittagong Hill Tracts remains murky. The compensation theory, in this case, appears more plausible.

The Dinajpur district too was divided by the Radcliffe Line, and the division went far beyond cartographic abstraction. It physically cleaved entire towns, homes, and marketplaces. The town of Hili was bisected. Even today, residents speak of Hili in Bangladesh, though technically no such administrative unit exists within Bangladesh except for a railway station. The actual town lies in India, while its adjoining region, now renamed Hakimpur, remains in Bangladesh.

Enclaves, divisions, and forgotten communities

Yet perhaps the most surreal consequence of Radcliffe's hurried demarcation was the creation of enclaves, known locally as chhit mahals. These were isolated land fragments of one country embedded within the other. A total of 162 Indian enclaves existed within East Pakistan, while East Pakistan had 51 enclaves inside Indian territory.

These enclaves were cut off from state services and infrastructure. People in the enclaves had no access to electricity, roads, schools, or police services. Some enclaves were surrounded by counter-enclaves, forming an absurd chain of a village inside another village, which was inside another country.

The origin of these enclaves goes back centuries. Their formation can be traced to complex land exchanges between the Mughal Empire and the Kingdom of Cooch Behar. The Cooch Behar was a princely state under the British, often engaged in territorial negotiations and disputes with Mughal officials. Some of these enclaves were the byproduct of those conflicts or were granted as part of friendly wagers.

These irregularities persisted under British colonial rule. When Cooch Behar formally joined India in 1949, the enclaves were left unchanged. Radcliffe's commission, operating under intense time pressure and armed with incomplete maps, paid little attention to these geographical anomalies.

For the tens of thousands who lived within these patches of land, life entered an enduring state of limbo. They held citizenship on paper but had to cross international borders just to reach their own countries. There were no official crossings, no visas, and no recognition.

Law enforcement agencies could not enter. Schools could not be built. Development projects were impossible. Many residents had no identity documents, no birth certificates, and no access to the judiciary. Some were rendered effectively stateless, living in political and legal shadows.

Following decades of diplomatic gridlock, and pressure from grassroots campaigns and human rights advocates, the situation was resolved when, in 2015, the India–Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement was implemented, marking the end of the enclave era.

The agreement allowed for a mutual exchange of enclaves and the formal absorption of residents into their respective states. Thousands were finally granted citizenship, access to services, and a voice in the democratic process.

By then, however, much of the damage had been done. Generations had grown up without schools or hospitals. Families were split, land ownership was uncertain, and trauma became intergenerational. The disruption caused by the Radcliffe Line was not merely bureaucratic.

Sylhet's referendum and the unfinished story of partition

While all this was happening on the Bengal frontier, in the eastern part, Sylhet was facing another issue. Sylhet was once part of the Bengal province under British India. However, the British administration detached Sylhet from Bengal and merged it with the Assam Division to create the new Assam Province.

Although administratively a part of Assam, Sylhet retained deep cultural, linguistic, and economic ties with Bengal.

As part of the Mountbatten Plan, a referendum was held on 6 and 7 July 1947 to determine Sylhet's future. The voter turnout was reportedly over 93 percent, with 2,39,619 people voting in favor of joining Pakistan and 1,84,041 opting to remain with India.

Despite this majority, several parts of Sylhet, most notably Karimganj, which had a Muslim-majority population, were retained by India following last-minute political interventions.

This discrepancy between the democratic outcome of the referendum and Radcliffe's eventual boundary decisions created longstanding grievances among Sylheti communities, many of whom found themselves divided from their cultural homeland and questioned their national identity and place of belonging.

The border also cut through the ancestral lands of Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo people in the surrounding hill regions, disrupting centuries of integrated trade, seasonal migration, and cultural exchange.

In the end, the Radcliffe Line was more than a border. It was a wound carved across landscapes, histories, and identities. Its jagged legacy still haunts the lives it divided and the maps it reshaped.

The ink on the Radcliffe Award has long since faded, but its imprint endures, in the names forgotten, in the unresolved ache of those still seeking belonging across the lines. Nearly eight decades later, the human cost of these choices continues.

As newer generations try to make sense of inherited borders and buried histories, the question remains: can lines drawn in haste ever be fully undone?

Comments